Vinita Damodaran

Vinita Damodaran

Professor Vinita Damodaran is a historian of modern India, interested in sustainable development dialogues in the global South. Her work ranges from the social and political history of Bihar to the environmental history of South Asia, including using historical records to understand climate change in the Indian Ocean World. She is particularly interested in questions of environmental change, identity and resistance in Eastern India. She is the director of the Centre for World Environmental History at the University of Sussex in England. She is also co-editor of the Palgrave series in World Environmental History.

Thoughts on working with the Gwillim Archives

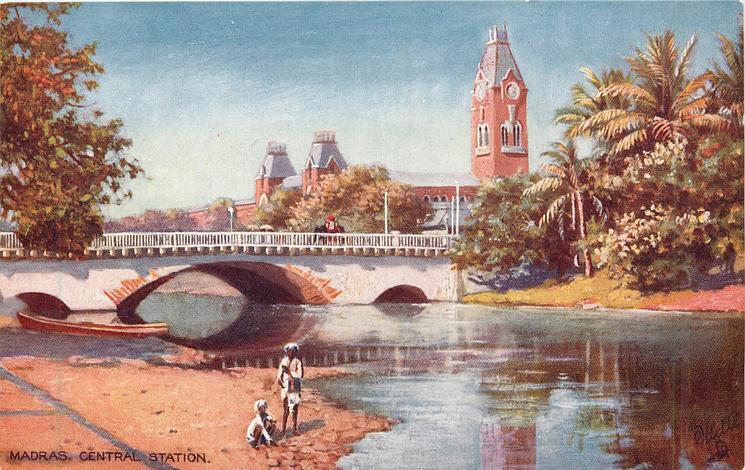

Working with the Gwillim Archives has been very productive for my own research. As a historian of India’s environmental history, I have mainly researched Eastern India and it was a pleasure to work with archives on South India. The sisters conjured up a landscape that was green and verdant most of the time, hot in the summer, awash with rains in the monsoon. They evoked a memory in me of growing up in India in the 1960s, of visiting Madras, a decaying post-colonial city with its grandiose British period architecture and the vibrant life of the beach. The smell of jasmine and mimosa rather like the sisters noted hung in the air, strung up in many garlands sold by hawkers adorning the hair of the ladies perambulating on the beach. I remember arriving by train after a long overnight journey from Delhi at the historic Madras central railway station designed by the architect George Harding in the nineteenth century, to be struck by the sight of the river.

The Cooum river that flowed by it was by then heavily polluted, a mere trickle. For centuries, the river had been the economic heart of the city, a clean river, suitable for boats and fishing. It had played a role in the maritime trade between the Roman empire, South India and Sri Lanka. This was a topography very different from that described by the sisters. The Adayar river they describe originating near the Chembarambakkam Lake in Kanchipuraam district, is one of the three rivers that runs through Madras and joins the Bay of Bengal at the Adyar estuary. Highly polluted today, as most of the waste from the city is drained into this river, both it and the Cooum nowhere resembled the rivers that the sisters had described and ones I would have loved to see it in their past glory.

The sisters wrote evocatively on the hydrogeography of Madras.

We have four Rivers in this place none of them navigable within some miles of this place & then only for boats - They are very shallow streams, but broad when there has been rain & the banks rich with wood in many parts, they wind about this plain in a most irregular manner & there are a great many Bridges over them, besides innumerable fords which being causeways well made in the dry seasons are quite safe & we seldom go out to dinner without passing one two or three of these. These Rivers run into the Sea at this place some of them come down the country 40 or 50 miles, & they enliven the country exceedingly The great beauty of this place is that if you quit the sea side you have always a river on one hand or the other, or else a tank, by which you are to understand a Lake, partly natural, but aided by art the dams being carefully kept up; Some of these tanks are many miles long & are very fine pieces of water - many of the houses are built on the banks of them with flights of steps to the water.

Despite being heavily polluted the Adayar river collects surplus water from about 200 tanks and lakes, small streams, as well as rainwater and drains in the city, with a combined catchment area of 860 square kilometres (331 sq mi). It still has boats and provides fish.

The tanks were interesting structures. The term applied to artificial ponds or lakes, 'made either by excavating or banking, which sometimes breach during the wet season, and dry up altogether in the hot weather' (Aditya Ramesh, 2018 ). In Tamil, tanks continue to be known as eris or kulams.

Maintained through an elaborate system of patronage and client relationships many tanks had deteriorated over time. Railways, colonial rule and land reclamation all were to blame for this. The famines of the nineteenth century had reinvigorated the importance of maintaining tanks but this was taken on board only briefly by the colonial administrators. Under the impetus of urbanisation post-independence there was a further deterioration. Flood plains were built on, the urban poor relocated to flood-prone marshlands, urban water bodies filled for ‘making bus stops, housing projects, dump yards and resettlements sites’ (Karen Coelo and Nitya Raman, 2013). All this has made Madras, now Chennai, much more susceptible to flood damage, and the city indeed in the twentieth century has had some serious flooding episodes - in 1910, 1943, and more recently in 2015 when the flooding submerged large parts of it. Some of this has to do with climatic factors and cyclonic activity but disregard for hydro ecologies and a rush for urban development by local agencies has led to the current urban problem. Ecological and social vulnerabilities are aligned and the poor in these regions have been disproportionately affected.

As the pressure on land increases due to population and demand, the intensification of agriculture will lead to further pressure on water sources, soil erosion and biodiversity loss. Indian agricultural and environmental policies as argued in a recent paper should aim ‘at supporting farmers in the implementation of sustainable intensification measures to minimize biodiversity losses and to foster soil carbon sequestration as a means to improve soil fertility and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture.’ (Hintz, et.al, 2020) With two-thirds of India’s population still dependent on agriculture, the livelihoods of its people and their well being depend on a sustainable environment.

All these thoughts strike me as I read the sisters’ archives to uncover the environmental history information of Madras in the early nineteenth century. The ways we have changed our landscapes is apparent for us to see and our manuscript sources reveal the true nature of it.

Further Reading

Karen Coelo and Nitya Raman, 'From the frying pan to the flood plain; Negotiating land, water and fire in Chennai’s development’, in Anna Rademacher and K. Sivaramakrishnan, eds., Ecologies of Urbanism in India: Metropolitan Civility and Sustainability, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2013.

Aditya Ramesh, ‘The value of tanks: maintenance, ecology and the colonial economy in nineteenth-century south India’,Water History, 2018.

R. Hinz, T. B. Sulser, R. Huefner, D. Mason-D’Croz, S. Dunston, S. Nautiyal, C. Ringler, J. Schuengel, P. Tikhile, F. Wimmer, R. Schaldach, 'Agricultural Development and Land Use Change in India: A Scenario Analysis of Trade-Offs Between UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),' Earths Future, Volume 8, Issue 2, February 2020.