Minakshi Menon

Minakshi Menon

Minakshi Menon is a member of Research Group Krause, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin, where she leads a Working Group on the famous Dutch herbal, the Hortus Indicus Malabaricus - “Hortus Indicus Malabaricus: the Eurasian Life of a Seventeenth-Century 'European' Botanical Classic”. Menon is working on a monograph with the working title, Empiricism’s Empire: Natural Knowledge Making, State Making and Governance in East India Company India, 1784-1830. She recently edited a special issue of the journal South Asian History and Culture, vol. 1-18 (2021).

Reflections on the Gwillim Letters

Elizabeth Gwillim was a percipient correspondent. Her letters, rich in details about household management, the latest fashion in caps and gowns, and observations on the natural world, also reveal what the anthropologist, Ann Laura Stoler, once called a “discursive density around issues of sentiment.” Lady Gwillim reflects upon and moralizes about private feelings and their public consequences, about racially-inflected sensibilities, about the psychic effects of colonization on both colonizer and colonized. It shouldn’t surprise us, then, to find her riding about Madras, acutely observing emerging new subjectivities among the colonized. Here she is writing to her mother, Esther Symonds, soon after her arrival in Madras.

Is not it a strange thing to see ourselves thus masters of a place? – you never meet an English person but in a carriage or in a Palankeen –The Sepoys that is the black soldiers have all the manners of ours even now when I see them so often regiments of them whether horse or foot I cannot help being surprized when I pass them & look back at the black faces drilled by our people they have so much the same air & they think so much of themselves that there is no danger of their befriending their country men – I used in my morning rides to pass the Camp we had here for some time & I was much diverted to see the Corporals drilling the awkward squads – & young beginners. so completely Corporals exactly the airs and affectation of those in the Park.

A reader, even one ever-so-slightly acquainted with postcolonial cultural critique, will recognize the phenomenon described. It has been theorized, famously, by Homi K. Bhabha as “mimicry”, “the desire for a reformed, recognizable Other, as a subject of a difference that is almost the same, but not quite.” (The Location of Culture. London and New York: Routledge, 1994). Bhabha’s sentence neatly captures both the colonial anxieties and the subversive effects produced by the civilizing mission. The colonizers’ will to reform, to confer the benefits of European Reason on their subjects produces a condition of ambivalence. It was imperative that “mimic men”, schooled to be “almost the same but not quite”, remain subjects of the British empire. But would they? Were the British to gift the Indians the British Constitution could they continue to rule? Bhabha helps us recognize the fear in Gwillim’s confident assertion that British-trained sepoys would never return to the dark side. The force of his analysis lies in its insistence that mimicry is always partial – the Anglicized can never be the English. Such partial presence necessitating continuing colonial control, carries the ever-present threat of disavowal. What lies behind colonial mimesis? You cannot know. And it is this uncertainty, I suggest, that produces the astonishing language of Mary Symonds’ letter to her botanical correspondent, Reginald Whitely.

A purported note of gratitude for a gift received, the letter mockingly reproduces Black English as slavish mimesis. The black servant’s anxiety to please, to respond immediately to the language of command (“I directly make sigiram send Bullock bandy get Blacktown dirt…”), guarantees the security of Britain’s empire. Or does it?

"Black English"

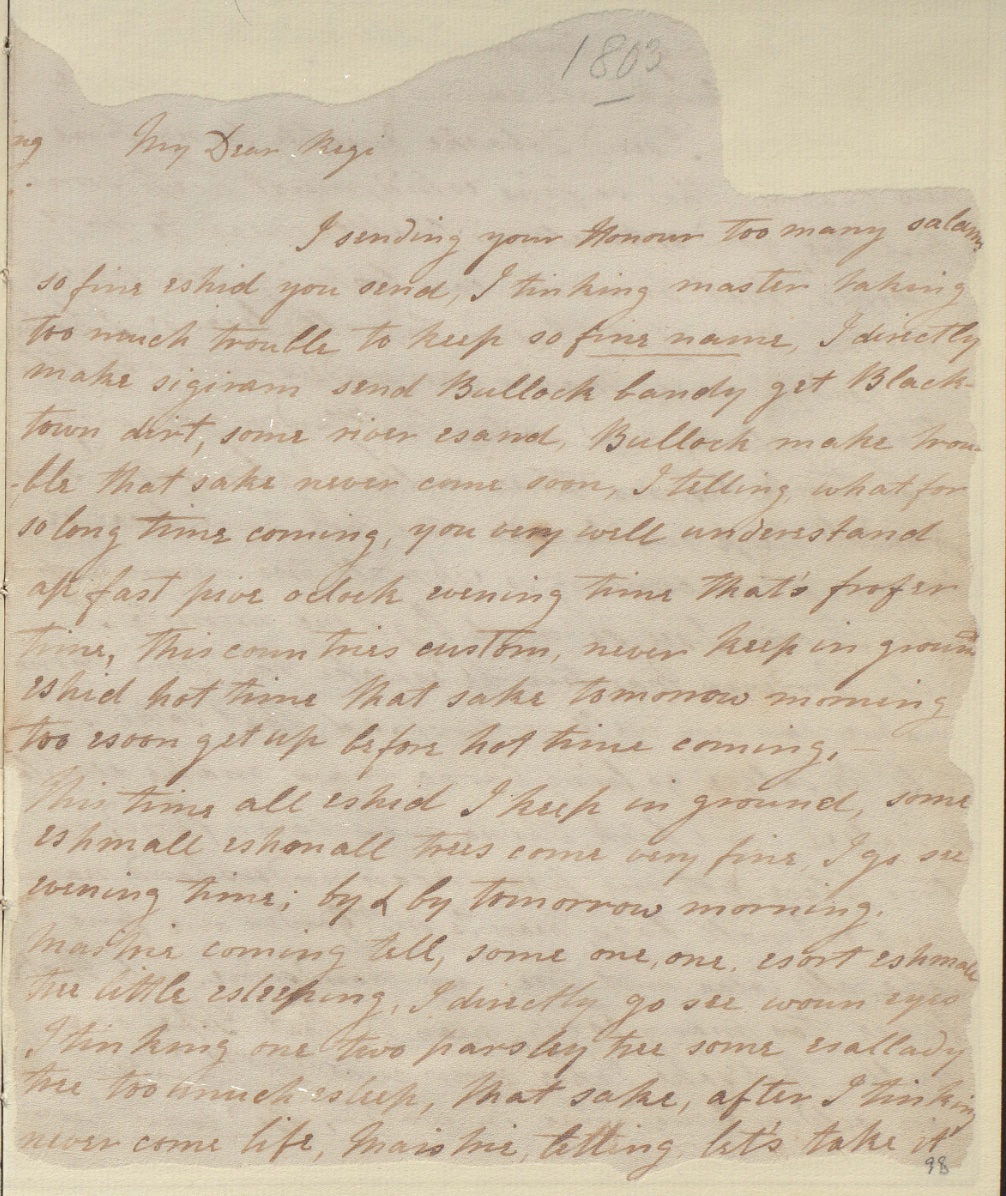

My Dear Regi

I sending your Honour too many salams so fine eshid you send, I tinking master taking too much trouble to keep so fine name, I directly make sigiram send Bullock bandy get Blacktown dirt, some river esand , Bullock make trouble that sake never come soon, I telling, what for so long time coming, you very well understand at past five oclock evening time that's proper time, this countries custom, never keep in ground eshid hot time that sake tomorrow morning too soon get up before hot time coming.

This time all eshid I keep in ground, some eshmall eshmall tree come very fine, I go see evening time; by & by tomorrow morning, maistrie coming tell, some one, one esort eshmall tree little esleeping, I directly go see woun eyes I tinking one too parsley tree some esallady tree too much esleep, that sake, after I tinking never come life, Maistrie…

The “eshid” refers to bags of seeds that Whitely sent the sisters. The waggish Whitely, who lettered the bags in imitation Chinese characters, is punished with a sample of Black English —a fitting retort to a metropolitan unaware of the parlousness of colonial mimicry. Symonds, writing as the black servant, having taken charge of the proceedings, places the seeds in the ground to help them germinate (“…I tinking one too parsley tree some esallady tree too much esleep, that sake, after I thinking never come to life…”), afterwards quickly dispatching the resident dubash to find the “China man” to decode the “Chinese” name of the plant.

Symonds, again the black servant, explains that ingratiating yourself with Master and Mistress is easier done if you can whole-heartedly enter into their interests. You may have the expertise needed to expel serpents from the mistress’s garden – build a nullah – but all she wants is a scientific identification of the cat that ravishes her fowls and sheep. This nondescript, once killed, is propped up to be figured, and then identified as a “lynx”; but, much more usefully, transformed into a fine curry for the palki-bearers… (Judging from Mary’s description, the “lynx” was probably the Asian palm civet (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus). Palm civets are ubiquitous in Kerala, where I'm from. They overran my grandmother’s house in Kochi where I lived as a child, in mortal dread of their claws and nauseating secretions.)

The last paragraph of the letter, voicing Mary Symonds, and Mary Symonds as black servant, adjures Whitely to make sense of the language of the letter. The British, it cajoles (fuzzle), must learn the native idiom or risk losing control: “I think after too much trouble I take, Master Regi never make fuzzle (effort), thats sake I telling Mrs must make little Gentoo [Hindu] writing; I send one Cajan [strip of plam leaf], if Master never find that Cajan writing, then must keep on more…”

And if not? A prescient warning for Company rule, “[b]ad fun”, a thorough trimming, will inevitably follow: “[B]ut if Master make hungry upon me directly cut off ears, cut him neck estrong wound” [.]