Confronting a Colonial Archive

What is an archive?

An archive is a collection of documents that provides information about a place, institution, person, or group of people. Documents have been preserved for this purpose for centuries, from the earliest cuneiform tablets and scrolls, to handwritten letters, to the tax returns of modern companies.

Until recently, at least in the Western world, documents have been considered as passive containers for information that was preserved and passed on by archivists. Archivists were also perceived as neutral - they simply made documents available to people who wanted to look at them.

Over the past 20 years, modern scholars have begun to highlight the fact that archives have always been sites of power. The documents collected over time have generally been the records of people in power - kings and queens, governments, dominant religions. These records are preserved selectively by the ruling classes to justify their decisions, to maintain their power, and to tell the story they wish to tell.

Archivists are also implicated in this power dynamic, because they choose which donations to accept and to reject. They can highlight certain collections and neglect others. These decisions have enormous influence over cultural memory and identity, because the records we save define who we are - our values, our history, and our present.

Legacies of Colonialism

Like most Western universities, McGill was built on a legacy of colonialism, and physically constructed on the traditional lands of the Haudenosaunee and Anishinabeg nations. Its founder, James McGill, was one of thousands of Europeans who settled in Canada in the late 18th century, as part of Europe’s ongoing project to colonize other parts of the world. As such, the archives that were collected by generations of archivists at McGill tend to reflect the colonial point of view.

The last few years have seen a movement in the archival world not only to acknowledge the historic and ongoing violence of colonialism, and the complicity of our collections in this violence, but also to consider how we can use archival records to confront this legacy head on.

Reading between the Lines

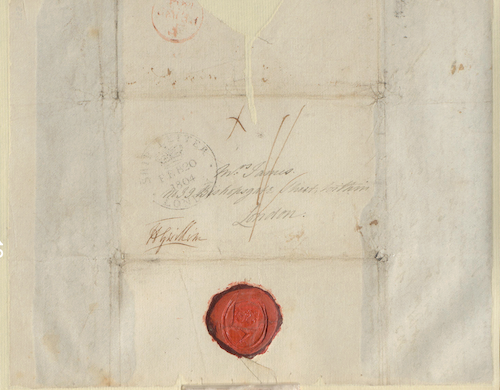

The Gwillim archives are an example of a colonial archive. Elizabeth Gwillim and her sister Mary Symonds were English women who travelled to India when Elizabeth’s husband was appointed to the supreme court in Madras. This court was established by the British after the East India Company had forcibly gained control over much of the country.

Taking the Gwillim material at face value, scholars might learn about the observations and activities of British people in South India.

Using a strategy to subvert this legacy - ‘reading between the lines’ - de-centres the colonial narrative and the experience of settlers, focussing instead on what these collections can tell us about the lives, practices, history, and experiences of colonized peoples.

Shifting the focus

Colonial collections detail the lives and work of colonizers; in order to read between the lines, we must first understand the colonial context in which the records were created, and then actively search for what was left out or not the main focus of these records.

In the Gwillim archives, this means combing through the hundreds of letters that Elizabeth and Mary sent back to their family in Britain, to locate their descriptions of the practices, ceremonies, and dress they encountered in Madras (now Chennai). It means focussing on the backgrounds of Elizabeth and Mary’s paintings, to analyze the people, buildings, and landscapes included there. Most importantly, it has meant working with researchers and scholars in India, with North American scholars who specialize in Indian history, and individuals who identify as members of the South Asian diaspora, to learn about what value they have found in this collection.

Through this shifting of focus, from colonizers to colonized, we are able to begin the work of adding traditionally underrepresented voices to the Western historical record, and confront the legacy of colonialism.

We have framed our work with the Gwillim archives as confronting colonialism. We acknowledge that our project is not exhaustive, and that the work of confronting the colonial legacies of our collections is only just beginning. We hope that the exhibits in this website will encourage visitors to engage with this complicated material in a thoughtful, constructive way, and that this project may serve as a model for highlighting underrepresented voices in other colonial collections.

Lauren Williams (she/her), Curator of the Blacker Wood Natural History Collection, McGill Library. I am a white settler living on the unceded territory of the Kanien'keha:ka people.