Painting nature

Birds, fish and flowers

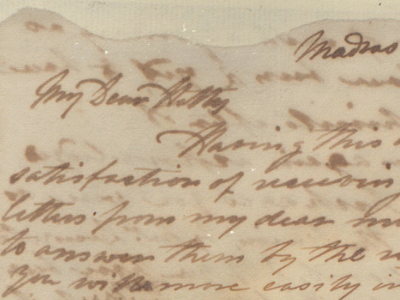

India in the 18th century saw the arrival from Britain of an increasing number of educated women from the upper and middle classes, adding to those from working class backgrounds who had been present from the establishment of the East India Company in 1603.

These educated women provided a foundation for the informal transmission of knowledge. While women played no part in professional bodies and scientific societies, they transmitted and popularised information through their letters, published accounts and illustrations.

The chief science that women claimed as their own was botany. This meshed with women’s traditional concern with medicinal plants, gardens and the propagation of plants both native and foreign. Both sisters were interested in gardening and both participated in plant exchanges with nurseries in England.

Though the sisters were not unique in their interests and achievements, they were, however, exceptional in the quality of their work, which was outstanding among amateurs, Elizabeth’s depiction of birds especially so.

Based on the Gwillim Research Project online symposium presentation by Dr Rosemary Raza, London UK.

Painting birds

Before the development of photography, naturalists classified birds based largely on depictions by artists. Like most bird artists of the period, Elizabeth Gwillim painted birds in profile. She was skilled in the placement and colouration of feathers, essential to bird identification. She was particularly inspired by the English engraver Thomas Bewick, author of British Birds (1797-1804), and the detailed backgrounds in some of her paintings reflect his practice of including scenes of daily life in his books. This painting of a rooster shows a detail of stables in the background to the left of the bird.

Elizabeth Gwillim's letters and paintings show a selection of the birds that she saw around early 19th-century Madras (present day Chennai). In all, she painted 104 species of birds, which included those she observed in her gardens, and those brought to her by professional Indian bird catchers. These men not only caught the birds, but also held them when they were being painted, and cared for those kept in cages, making possible Gwillim's lively portrayals of her subjects. Not all the birds she painted were native to the area; some were imported by bird fanciers or as game birds by hunters.

Studying botany

In Madras, Elizabeth Gwillim studied botany with the missionary Dr Johann Peter Rottler. Learning Indian botany not only helped her identify the plants in her garden, it was also important to her study of the Telugu language spoken by many people in Madras. Because there were so many plant metaphors in the literature, knowing the local flora was essential to reading the texts.

Mary Symonds wrote that her sister also consulted 'native Doctors' for the common names and Brahmins for the Sanskrit names of plants, and searched for Latin scientific names in the copy of Miller's Gardener's Dictionary she had brought with her.

Though they likely painted many more flowers and plants, just twelve botanical paintings remain in the Blacker Wood collection at McGill. When Dr Casey Wood bought the albums of flowers, fish and birds for the McGill Library from a London book dealer in 1925, he was told that occasional paintings from the collection had been sold for framing or for decorating fire screens. This was probably the fate of the finest examples of the sisters' botanical art.

Learn more about the initial acquisition of the paintings by Dr Casey Wood in Podcast Episode 2.